2026 – Pilot Projects to Scalable Systems

2026 is the year emerging markets must rethink Waste, Energy, and Urban Growth.

The start of a new year is more than a reset—it’s a moment to decide what we do differently.

As 2026 begins, emerging markets stand at a defining crossroads. Urban populations are expanding rapidly, energy demand continues to rise, and waste volumes are growing faster than infrastructure can manage. These pressures are not new, but the consequences of inaction are becoming harder to ignore.

This year, the conversation must shift from managing symptoms to solving root causes.

For too long, waste has been treated as a downstream problem—something to collect, dump, or burn out of sight. At the same time, energy planning has focused on adding capacity without fully addressing reliability, affordability, or environmental impact. In reality, these challenges are deeply connected.

That connection is where waste-to-energy (WTE) becomes increasingly relevant.

Why 2026 Feels Different

What makes this year distinct is not technology—it’s urgency.

Cities are running out of landfill space.

Methane emissions from waste are now recognised as a major climate risk.

Power grids are under strain from growing demand and aging infrastructure.

WTE directly addresses all three. It reduces landfill dependency, cuts methane at the source, and produces reliable, base-load power that complements solar and wind. It is not a silver bullet, but it is a proven, practical tool that many emerging markets can no longer afford to overlook.

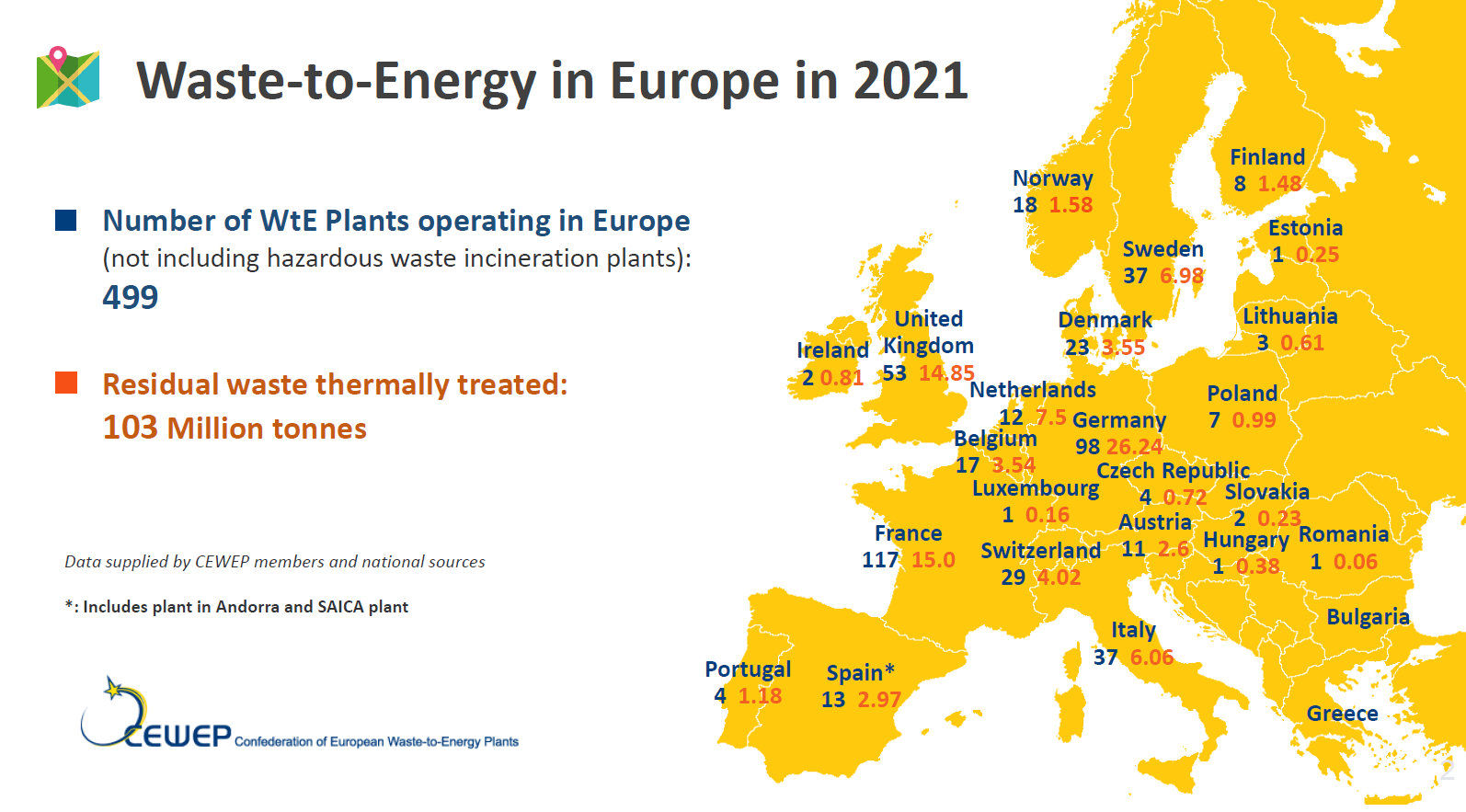

CEWEP EU Map for WTE 2021

From Pilot Projects to Scalable Systems

One of the biggest shifts needed in 2026 is moving beyond isolated pilot projects.

WTE works best when it is part of a wider urban system—linked to waste collection reform, recycling strategies, grid planning, and long-term policy support. Cities that succeed are those that plan WTE not as a standalone facility, but as core infrastructure, much like water treatment or power generation.

This requires collaboration:

- Governments setting clear, stable frameworks

- Developers delivering bankable, right-sized solutions

- Communities being engaged early and transparently

When these elements align, WTE stops being controversial and starts being transformative.

A Practical Path Forward

2026 should be the year emerging markets focus on implementation over intention.

That means:

- Prioritising waste reduction and recycling alongside energy recovery

- Choosing proven technologies suited to local waste composition

- Planning projects that are financially viable, environmentally sound, and socially accepted

Most importantly, it means recognising that waste is no longer something cities can afford to ignore or postpone. It is an untapped resource—one that can support cleaner cities, stronger energy systems, and more resilient economies.

Looking Ahead

The question for 2026 is no longer “Is waste-to-energy right for emerging markets?”

The real question is “How quickly can it be done well?”

This year offers an opportunity to move from discussion to delivery. The cities that act decisively will not only solve today’s waste problems—they will define the next generation of sustainable urban growth.

Here’s to a year of smarter choices, practical solutions, and real progress.

Read More

Could Waste-to-Energy Be Key to Pakistan Hitting Its 2030 Climate Goals?

Pakistan remains one of the most polluted countries in the world, ranking as the second most polluted nation in 2023. This level of pollution has a serious impact on public health, cutting the average Pakistani’s life expectancy by nearly four years. Industrial activity, vehicle emissions, and the open burning of waste—especially in major cities like Karachi, Lahore, and Peshawar—are among the main drivers of poor air quality. The situation has steadily worsened, underscoring the urgent need for stronger environmental policies.

A major portion of Pakistan’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions comes from the energy sector, which accounts for about 46% of total emissions. Electricity generation, transport, and industrial energy use rely heavily on fossil fuels, especially coal, natural gas, and oil. Although Pakistan has committed to sourcing 60% of its energy from renewables by 2030, progress has been slow.

Hydropower, a cornerstone of the country’s renewable ambitions, takes years to build before contributing to the grid. Solar and wind energy have grown—particularly in Sindh and Balochistan—but limited transmission capacity prevents these technologies from reaching their full potential. Pakistan currently has 36 wind plants with 1,838 MW of installed capacity, yet many operate below optimal levels due to grid bottlenecks.

The Gharo–Keti Bandar wind corridor, with an estimated potential of 50,000 MW, highlights the scale of opportunity. Still, 27 additional wind projects (1,875 MW) remain unapproved because the grid cannot accommodate them. Solar adoption has expanded through net metering, helping households and businesses reduce dependence on the national grid. However, these gains are not enough to achieve Pakistan’s 2030 energy transition targets.

In this context, Waste-to-Energy (WtE) is emerging as a practical extension of Pakistan’s climate and energy strategy. WtE tackles two issues simultaneously: it generates power while addressing the country’s worsening waste problem. These projects reduce emissions, improve resource efficiency, and directly support cleaner and more sustainable cities.

Pakistan’s most notable WtE success so far has been bagasse-based energy. As one of the world’s largest sugarcane producers, the country generates substantial bagasse, which sugar mills use to produce heat and power through cogeneration. Much of this electricity is supplied to the grid during the crushing season. Pakistan’s total potential for bagasse-based power is estimated at over 2,000 MW, though only a portion is currently delivered to the grid. Because bagasse is seasonal, Pakistan still needs more consistent, year-round WtE solutions.

Beyond bagasse, Pakistan’s agricultural sector produces large volumes of biomass—wheat straw, rice husks, and cotton stalks—which could also be converted into energy. With about 84 million tons of agricultural residues generated annually, much of which is burned in fields, the potential for biogas and biomass power plants is significant. Yet, only 249 MW of bagasse/biomass capacity is connected to the national grid, far below what is possible.

To improve environmental performance, the government launched the Clean Green Pakistan initiative in 2019, focusing on waste management, sanitation, and urban greening.

Pakistan’s cities collectively generate 49.6 million tons of municipal solid waste (MSW) each year, increasing at 2.4% annually. Most of this ends up in landfills or informal dumps, posing serious environmental and health risks. Karachi alone produces 16,500 tons of MSW daily, followed by Lahore with 7,690 tons. Globally, WtE is a proven technology, and Pakistan could use it to both manage waste and generate renewable energy. WtE systems—whether incineration, anaerobic digestion, or gasification—could substantially reduce landfill use and contribute clean power to the grid.

Under the Clean Green Pakistan initiative, Punjab launched the country’s first major WtE project in Lahore, a 40 MW plant designed to process 2,000 tons of MSW per day. Developed by a Chinese consortium, the project has faced delays and is now expected to begin commercial operations in 2026. A second WtE plant of similar capacity has already been proposed for Lahore.

In Karachi, several WtE initiatives were announced in 2022 through public-private partnerships. These projects aim to process 6,000–8,000 tons of waste daily, generating up to 250 MW for K-Electric. Companies including Babcock & Wilcox and Mondofin UK, Green Waste Energy, Khan Renewable Energy and Engro Energy are leading the effort, though the project has since stalled facing various challenges they are still in the feasibility stage.

Pakistan has made meaningful progress in renewable energy and waste management, but far more is required to meet its 2030 climate goals. WtE aligns closely with the country’s national climate policies and international obligations, including the Paris Agreement. Scaling up these projects is essential, especially as Pakistan continues to grapple with rapid urbanisation, expanding waste streams, and rising emissions.

Ultimately, waste-to-energy is more than an energy solution—it is a vital part of improving waste management, reducing pollution, and achieving Pakistan’s broader environmental and climate objectives. Growing these initiatives will be critical as the country works toward a cleaner and more sustainable future.

Read MoreCan green hydrogen save a coal town and slow climate change?

A smokestack stands at a coal plant on Wednesday, June 22, 2022, in Delta, Utah. Developers in rural Utah who want to create big underground caverns to store hydrogen fuel won a $504 million loan guarantee this spring. They plan to convert the site of the plant completely to cleanly-made hydrogen by 2045. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)

DELTA, Utah (AP) – The coal plant is closing. In this tiny Utah town surrounded by cattle, alfalfa fields and scrub-lined desert highways, hundreds of workers over the next few years will be laid off – casualties of environmental regulations and competition from cheaper energy sources.

Yet across the street from the coal piles and furnace, beneath dusty fields, another transformation is underway that could play a pivotal role in providing clean energy and replace some of those jobs.

Here in the rural Utah desert, developers plan to create caverns in ancient salt dome formations underground where they hope to store hydrogen fuel at an unprecedented scale. The undertaking is one of several projects that could help determine how big a role hydrogen will play globally in providing reliable, around-the-clock, carbon-free energy in the future.

What sets the project apart from other renewable energy ventures is it’s about seasonal storage more than it’s about producing energy. The salt caves will function like gigantic underground batteries, where energy in the form of hydrogen gas can be stored for when it’s needed.

“The world is watching this project,” said Rob Webster, a co-founder of Magnum Development, one of the companies spearheading the effort. “These technologies haven’t been scaled up to the degree that they will be for this.”

In June, the U.S. Department of Energy announced a $504 million loan guarantee to help finance the “Advanced Clean Energy Storage” project – one of its first loans since President Joe Biden revived the Obama-era program known for making loans to Tesla and Solyndra. The support is intended to help convert the site of a 40-year-old coal plant to a facility that burns cleanly-made hydrogen by 2045.

Amid polarizing energy policy debates, the proposal is unique for winning support from a broad coalition that includes the Biden administration, Sen. Mitt Romney and the five other Republicans who make up Utah’s congressional delegation, rural county commissioners and power providers. Biden was set to announce new actions on climate change Wednesday during an event in Massachusetts at a former coal-fired power plant that is shifting to a renewable energy hub.

Renewable energy advocates see the Utah project as a potential way to ensure reliability as more of the electrical grid becomes powered by intermittent renewable energy in the years ahead.

In 2025, the initial fuel for the plant will be a mix of hydrogen and natural gas. It will thereafter transition to running entirely on hydrogen by 2045. Skeptics worry that could be a ploy to prolong the use of fossil fuels for two decades. Others say they support investing in clean, carbon-free hydrogen projects, but worry doing so may actually create demand for “blue” or “gray” hydrogen. Those are names given to hydrogen produced using natural gas.

“Convincing everyone to fill these same pipes and plants with hydrogen instead (of fossil fuels) is a brilliant move for the gas industry,” said Justin Mikula, a fellow focused on energy transition at New Consensus, a think tank.

Unlike carbon capture or gray hydrogen, the project will transition to ultimately not requiring fossil fuels. Chevron in June reversed its plans to invest in the project. Creighton Welch, a company spokesman, said in a statement that it didn’t reach the standards by which the oil and gas giant evaluates its investments in “lower carbon businesses.”

As utilities transition and increasingly rely on intermittent wind and solar, grid operators are confronting new problems, producing excess power in winter and spring and less than needed in summer. The supply-demand imbalance has given rise to fears about potential blackouts and sparked trepidation about weaning further off fossil fuel sources.

This project converts excess wind and solar power to a form that can be stored. Proponents of clean hydrogen hope they can bank energy during seasons when supply outpaces demand and use it when it’s needed in later seasons.

Here’s how it will work: solar and wind will power electrolyzers that split water molecules to create hydrogen. Energy experts call it “green hydrogen” because producing it emits no carbon. Initially, the plant will run on 30% hydrogen and 70% natural gas. It plans to transition to 100% hydrogen by 2045.

When consumers require more power than they can get from renewables, the hydrogen will be piped across the street to the site of the Intermountain Power Plant and burned to power turbines, similar to how coal is used today. That, in theory, makes it a reliable complement to renewables.

Many in rural Delta hope turning the town into a hydrogen epicenter will allow it to avoid the decline afflicting many towns near shuttered coal plants, including the Navajo Generating Station in Arizona.

But some worry using energy to convert energy – rather than sending it directly to consumers – is costlier than using renewables themselves or fossil fuels like coal.

Though Michael Ducker, Mitsubishi Power’s head of hydrogen infrastructure, acknowledges green hydrogen is costlier than wind, solar, coal or natural gas, he said hydrogen’s price tag shouldn’t be compared to other fuels, but instead to storage technologies like lithium-ion batteries.

For Intermountain Power Agency, the hydrogen plans are the culmination of years of discussions over how to adapt to efforts from the coal plant’s top client – liberal Los Angeles and its department of water and power – to transition away from fossil fuels. Now, resentment toward California is sweeping the Utah community as workers worry about the local impacts of the nation’s energy transition and what it means for their friends, families and careers.

“California can at times be a hiss and a byword around here,” city councilman Nicholas Killpack, one of Delta’s few Democrats, said. “What we I think all recognize is we have to do what the customer wants. Everyone, irrespective of their political opinion, recognizes California doesn’t want coal. Whether we want to sell it to them or not, they’re not going to buy it.”

The coal plant was built in the wake of the 1970s energy crisis primarily to provide energy to growing southern California cities, which purchase most of the coal power to this day. But battles over carbon emissions and the future of coal have pit the states against each other and prompted lawsuits. Laws in California to transition away from fossil fuels have sunk demand for coal and threatened to leave the plant without customers.

In Millard County, a Republican-leaning region where 38% of local property taxes come from the Intermountain Power Plant, two coal plant workers unseated incumbent county commissioners in last month’s Republican primary. The races saw campaign signs plastered throughout town and tapped into angst about the multimillion-dollar plans and how they may transform the job market and rural community’s character.

“People are fine with the concept and the idea of it being built,” Trevor Johnson, one of the GOP primary winners, said, looking from the coal plant’s parking lot toward where the hydrogen facility will be. “It’s just coal power is cheap and provides lots of good jobs. That’s where the hang-up is.”

Read MoreGreen hydrogen project receives $504 million DOE loan guarantee

A green hydrogen project in Utah has received a $504.4 million loan guarantee from the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office, the first guarantee awarded to a clean energy project in nearly a decade.

The Advanced Clean Energy Storage project will combine 220 MW of alkaline electrolysis with two 4.5-million-barrel salt caverns to store clean hydrogen.

The project is intended to capture excess renewable energy when it is most abundant, store it as hydrogen, and then deploy it as fuel for the Intermountain Power Agency’s IPP Renewed Project. The hydrogen-capable gas turbine combined cycle power plant would be incrementally fueled by 100% clean hydrogen by 2045.

The Advanced Clean Energy Storage project received a conditional commitment from LPO in April. This is the first time a green hydrogen project has received a loan guarantee from DOE.

The Utah project is planned to include retiring existing coal-fueled power generating units at the IPP site; installing new natural gas-fueled electricity generating units capable of utilizing hydrogen for 840 MW net generation output; modernizing IPP’s Southern Transmission System linking IPP to Southern California, and developing hydrogen production and long-term storage capabilities.

IPP would use renewable energy-powered electrolysis to split water into oxygen and hydrogen. The new natural gas generating units, expected to be supplied by Mitsubishi Power, would use 30% hydrogen fuel at start-up, transitioning to all hydrogen fuel by 2045 as technology improves. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power would be the off-taker for electricity produced by the facility.

50-fold increase

Across all its programs, LPO has attracted more than 70 active applications for projects in 24 states totalling nearly $79 billion in requested loans and loan guarantees as of the end of May.

With the closing of this loan guarantee, LPO now has $2.5 billion in remaining loan guarantee authority for Innovative Clean Energy projects.

“Accelerating the commercial deployment of clean hydrogen as a zero-emission, long-term energy storage solution is the first step in harnessing its potential to decarbonize our economy, create good-paying clean energy jobs and enable more renewables to be added to the grid,” Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said.

Green hydrogen plays an important role in the Biden administration’s goal of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050.

DOE’s National Energy Technology Laboratory determined that U.S. clean hydrogen production and use must increase 50-fold by 2050 to meet the country’s decarbonization goals.

Report findings noted while many opportunities exist for hydrogen’s growth, government leadership would be critical in achieving decarbonization goals. This would include tax credits and incentives, research, development and demonstration funding.

The DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy has announced its intent to issue a funding opportunity to analyze the potential for regional clean energy deployments, all in the name of reducing the cost of green hydrogen production from $5 per kilogram to $1 by 2030.

Additionally, President Biden’s FY 2022 budget request includes $400 million for hydrogen activities, compared to $285 million in FY 2021.

Green (or clean) hydrogen produced using renewable energy and electrolysis represents only 5% of the hydrogen produced in the U.S. due to its high cost. In comparison, the remaining 95% is produced using fossil fuels.

So-called “blue hydrogen” from natural gas incorporates carbon capture and storage. However, recent studies suggest the practice could produce even more carbon emissions in heat generation than natural gas alone.

Read More

Refuse Derived Fuel

What exactly is RDF? Is it a secondary product or a waste? And is it available on the open market as a cheap renewable fuel?

RDF is refuse-derived fuel and it is produced as an output from materials recycling facilities (MRFs). It is composed of treated residual waste that is not suitable for recycling.

Although the residual waste has been through a treatment process, the manufacture of RDF does not qualify as recovery and the RDF is still classified as waste. Unlike secondary fuels based on waste solvents, it does not have such a high calorific value as fossil fuels and cannot be used as a direct replacement for them. Instead, it is burned in energy from waste (EfW) plants. RDF is regulated in the same way as any other waste and can only be burned in an installation that complies with the requirements for waste incinerators, taken from the EU Industrial Emissions Directive.

Energy from waste can be classified as either disposal by incineration or recovery (code R1), based on whether its primary purpose is to produce energy or dispose of waste. The Waste Framework Directive distinguishes between disposal and recovery using a formula based on the efficiency of the plant. Defra explains this as follows.

The R1 formula calculates the energy efficiency of the municipal solid waste incinerator and expresses it as a factor. This is based on the total energy produced by the plant as a proportion of the energy of the fuel (both traditional fuels and waste) that is incinerated in the plant. It can only be considered recovery if the value of this factor is above a certain threshold. It is important to note that the calculated value arrived at via the R1 formula is not the same as power plant efficiency, which is typically expressed as a percentage.