Could Waste-to-Energy Be Key to Pakistan Hitting Its 2030 Climate Goals?

Pakistan remains one of the most polluted countries in the world, ranking as the second most polluted nation in 2023. This level of pollution has a serious impact on public health, cutting the average Pakistani’s life expectancy by nearly four years. Industrial activity, vehicle emissions, and the open burning of waste—especially in major cities like Karachi, Lahore, and Peshawar—are among the main drivers of poor air quality. The situation has steadily worsened, underscoring the urgent need for stronger environmental policies.

A major portion of Pakistan’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions comes from the energy sector, which accounts for about 46% of total emissions. Electricity generation, transport, and industrial energy use rely heavily on fossil fuels, especially coal, natural gas, and oil. Although Pakistan has committed to sourcing 60% of its energy from renewables by 2030, progress has been slow.

Hydropower, a cornerstone of the country’s renewable ambitions, takes years to build before contributing to the grid. Solar and wind energy have grown—particularly in Sindh and Balochistan—but limited transmission capacity prevents these technologies from reaching their full potential. Pakistan currently has 36 wind plants with 1,838 MW of installed capacity, yet many operate below optimal levels due to grid bottlenecks.

The Gharo–Keti Bandar wind corridor, with an estimated potential of 50,000 MW, highlights the scale of opportunity. Still, 27 additional wind projects (1,875 MW) remain unapproved because the grid cannot accommodate them. Solar adoption has expanded through net metering, helping households and businesses reduce dependence on the national grid. However, these gains are not enough to achieve Pakistan’s 2030 energy transition targets.

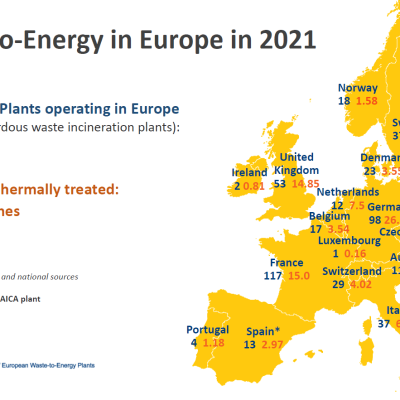

In this context, Waste-to-Energy (WtE) is emerging as a practical extension of Pakistan’s climate and energy strategy. WtE tackles two issues simultaneously: it generates power while addressing the country’s worsening waste problem. These projects reduce emissions, improve resource efficiency, and directly support cleaner and more sustainable cities.

Pakistan’s most notable WtE success so far has been bagasse-based energy. As one of the world’s largest sugarcane producers, the country generates substantial bagasse, which sugar mills use to produce heat and power through cogeneration. Much of this electricity is supplied to the grid during the crushing season. Pakistan’s total potential for bagasse-based power is estimated at over 2,000 MW, though only a portion is currently delivered to the grid. Because bagasse is seasonal, Pakistan still needs more consistent, year-round WtE solutions.

Beyond bagasse, Pakistan’s agricultural sector produces large volumes of biomass—wheat straw, rice husks, and cotton stalks—which could also be converted into energy. With about 84 million tons of agricultural residues generated annually, much of which is burned in fields, the potential for biogas and biomass power plants is significant. Yet, only 249 MW of bagasse/biomass capacity is connected to the national grid, far below what is possible.

To improve environmental performance, the government launched the Clean Green Pakistan initiative in 2019, focusing on waste management, sanitation, and urban greening.

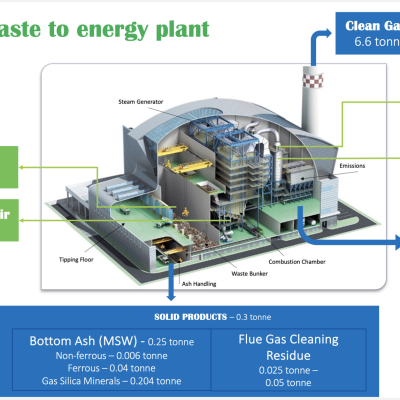

Pakistan’s cities collectively generate 49.6 million tons of municipal solid waste (MSW) each year, increasing at 2.4% annually. Most of this ends up in landfills or informal dumps, posing serious environmental and health risks. Karachi alone produces 16,500 tons of MSW daily, followed by Lahore with 7,690 tons. Globally, WtE is a proven technology, and Pakistan could use it to both manage waste and generate renewable energy. WtE systems—whether incineration, anaerobic digestion, or gasification—could substantially reduce landfill use and contribute clean power to the grid.

Under the Clean Green Pakistan initiative, Punjab launched the country’s first major WtE project in Lahore, a 40 MW plant designed to process 2,000 tons of MSW per day. Developed by a Chinese consortium, the project has faced delays and is now expected to begin commercial operations in 2026. A second WtE plant of similar capacity has already been proposed for Lahore.

In Karachi, several WtE initiatives were announced in 2022 through public-private partnerships. These projects aim to process 6,000–8,000 tons of waste daily, generating up to 250 MW for K-Electric. Companies including Babcock & Wilcox and Mondofin UK, Green Waste Energy, Khan Renewable Energy and Engro Energy are leading the effort, though the project has since stalled facing various challenges they are still in the feasibility stage.

Pakistan has made meaningful progress in renewable energy and waste management, but far more is required to meet its 2030 climate goals. WtE aligns closely with the country’s national climate policies and international obligations, including the Paris Agreement. Scaling up these projects is essential, especially as Pakistan continues to grapple with rapid urbanisation, expanding waste streams, and rising emissions.

Ultimately, waste-to-energy is more than an energy solution—it is a vital part of improving waste management, reducing pollution, and achieving Pakistan’s broader environmental and climate objectives. Growing these initiatives will be critical as the country works toward a cleaner and more sustainable future.